Natural treasures: A day-trip through the Ethiopian highlands

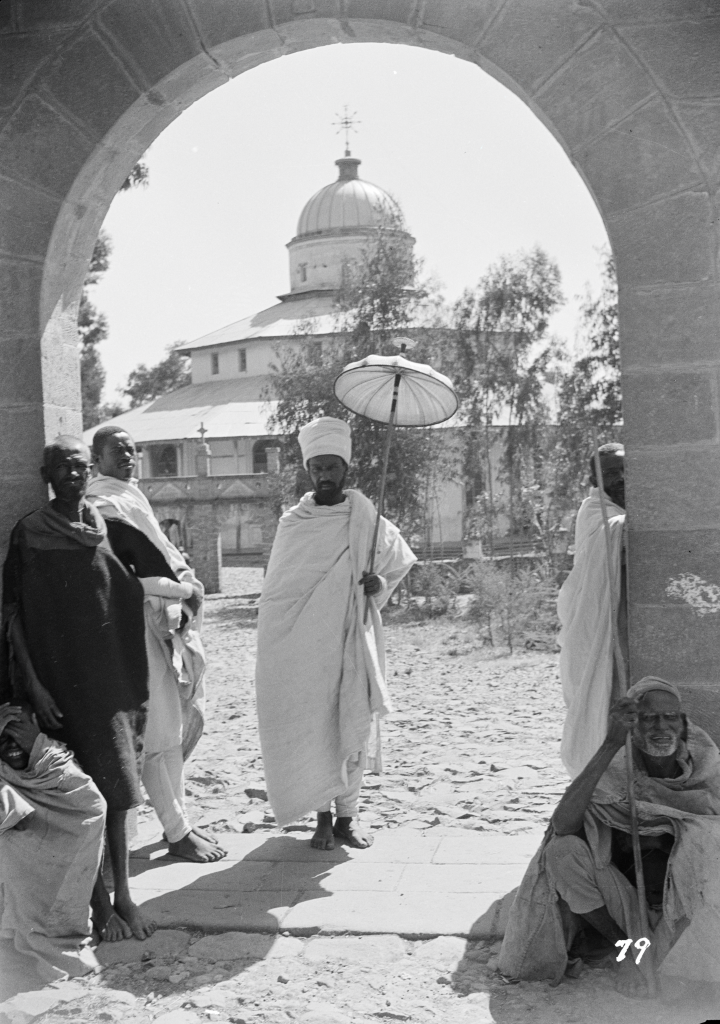

In the ethereal sunlight that blesses early mornings in Ethiopia’s high country, we walk a path under rare giants in the grounds of a monastery 700 years-old.

African sandalwood and juniper, red-flowering kosso and heavy-limbed figs mark our way through ribbons of incense to the church and meditation cave of a great saint.

If these old trees could talk. They couldn’t possibly tell the full history of Debre Libanos – one of Ethiopia’s most fabled holy sites. But, rooted as they’ve been to this cliff edge for generations – drinking from sacred falls and the minerals of ancient bones – they’d surely know some of her secrets.

“We call these our last warriors: They’re endangered in most parts of the country now,” says Zemede, an ethnobotanist from Addis Ababa University. He’s joined us – a researcher and a writer – to collect stories of traditional medicine in an area that, according to legend, is a special site of healing.

Unlike the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela or the island monasteries of Lake Tana to the north, Debre Libanos remains, for most outsiders, unheard of. And yet it offers all those things Ethiopia is travelled for: History, dramatic landscapes, unique wildlife, glimpses into an ancient culture, still lived.

For the country’s Orthodox Christians, it’s a hugely important pilgrimage. Thousands journey each year to worship at the cave of 13th Century Saint Tekle Haymanot; a miracle healer credited with bringing Christianity to the Shewa Kingdom, as these parts were known.

We’d travelled an easier distance – just a two-hour drive from the capital Addis Ababa. And our interests were more earthly. Though we’d soon find that traditional medicine, like most things in Ethiopia – ‘Land of Origins’ – is intimately bound with mythology and the spiritual world.

**

The road north is all-absorbing. Winding up and over the Entoto mountains, it gifts eagle views of the city we leave behind; one already 2,300 metres above the sea. Lean long-distance runners, hustled village scenes and sweeps of undulating farmland flicker by like moving frames of a film we can’t quite catch. This part of the country, with its fertile black soil, was once called the breadbasket of Ethiopia.

“But you have to look at fossils and seeds to know what was growing here before. There are no living trees that belong here now,” Zemede says. Population and grazing pressures, demand for timber and fuel-wood are usual culprits. “Now, we have only ‘talking trees’: ones thar make noise but are not actually very useful.”

From between Eucalpyts, bright barley and teff fields along the flat-tops or ambas of the Rift mountains, our road snakes lower into woody acacia scrub and red earth, past roadside stalls dangling coptic trinkets of carved pink soapstone – to the very edge of an enormous gorge. To one of those awesome (and very Ethiopian) vistas that snap you, with disconcerting clarity, to the realization you are the size of an ant.

Through the windscreen, we look down to the Jemma River; a tributary of the Blue Nile, cutting its long journey to Sudan through a valley of sesame and sorghum 1,000 metres below. A harem of gold-maned Gelada Baboons perch languidly on the precipice; their bleeding-heart breasts to the sun like monks in prayer themselves as we approach the old grove at the monastery gates.

There, we’re greeted by a guide; an older man wrapped in the cotton white Gabi of the highlands. He tucks our crinkled birr notes into the folds around him and tugs on a low leaf as he leads us along, past penitents and women selling baskets and worship candles. “This is African Cherry,” he says: “We call it the tree of life.”

These trees, some of Ethiopia’s last afromontane forest, have been fiercely protected by the monks and nuns or many hundreds of years. According to the old scripts, they’re like clothes for the church – or angels’ wings – sheltering the centre, holding a space for prayer.

Their secrets, still today, are heavily guarded and we wouldn’t be offered any more before we left. But we were given a tour of the new church, built by Emperor Haile Selassie in the early 60s (The original monastery was destroyed in 1532 by the army of Muslim conqueror Ahmad Gragn).

Then – and actually, as far back as the 1400s – Debre Libanos was the political centre of Ethiopia’s Orthodox church. A place of great influence until the Italian occupation, when a famously vicious attack led by Fascist general Rodolfo Graziani destroyed it completely.

Graziani – the ‘Butcher of Ethiopia’ as he became known – had learnt of a plot on his own life and ordered the massacre of 400 monks in revenge, along with anyone connected with the monastery ‘without distinction.’ It was one of a chain of atrocities that stretched to the capital and is remembered today as Yekatit 12. Within days, more than 30,000 Ethiopians were dead. Of Debre Libanos, the general reported home, ‘there remains no trace.’

The story is recounted beneath colourful stained-glass inside the new church – and the bones; the remains of bishops, scholars and pilgrims – lie to this day in mountain graves behind it.

Up a steep path there, too, is Tekle Haymanot’s cave: a mossy shrine with a trickle of holy water that is especially good for banishing stomach upsets and evil spirits. It is here, legend goes, that the Saint received the gift of eternal life from the angels after praying on one leg – fed only seeds by a bird – for seven years straight.

Image: Walter Mittelholzer. ETH-Bibliothek

From Debre Libanos, we were to make our way further along the lip of the gorge to meet an old friend in a town called Fiche. For years, Lakew had regaled us with expansive images of the ‘most incredible landscape’ and his regret at its missed tourism potential. “It’s untouched,” he’d say. “And do you know it’s the best hang-gliding launch spot in the world?”

We did not, of course, but we were about to see why with a coffee stop at the nearby Ethio-German Hotel.

A collection of stone-cold tukuls and one rustic traditional restaurant, the hotel – which seems to appear out of nowhere – commands some of the very best views in the country.

We sit in the sun, looking down and out over the great Jemma Gorge, cradling small cups of earthy, just-pounded buna. Black eagles and Lamergeyer circle below us – hang-gliding on the thermals – over a collection of thatched mud houses, a blue-roofed church and terraced farmland the colours of honeydew melon and straw.

This area is known for its abundant endemic birdlife – and all around us chimed smaller ones, their names like charms: Abyssinian Orioles and Sunbirds, Dusky Flycatchers and White-winged Cliff Chats, Banded Barbets and Firefinches.

We finish the customary three rounds of coffee – the last, a blessing for our way. Beside the birds and another family of baboons, the place was our own.

Fiche town, just a five-minute drive from the hotel, first appeared as a collection of traditional coffee shops, raw meat houses and worn hotels for the truck drivers making their way between Addis and Gojam in the north. But Sunday was market day and we soon found the road congested with goats and horse-drawn garries, garnished with pom poms and bells.

Lakew – 78, effervescent and as charming as ever – was to introduce us to a group of traditional and household herbalists. He’s just the bloke, he says. Aside from the fact that he’s shrinking: “The worst part of getting old, you know?” he’s a local and he “eats herbs like a goat.”

“And I’m compact!” he winks. Leaving the car to push on foot past tuk-tuks and wheelbarrows of papaya, we scramble to keep up.

In the market there are women roasting coffee and frankincense on hot coals beside clay pots and green beans, spices and herbs laid on ground sheets under parasols. The kebercho roots are smoked to keep nightmares at bay; sweet-smelling bundles of ariti are for expelling parasites, attracting honeybees too.

We head off-road between houses made of mud, resting donkeys and brightly painted doors. Our path opens up to yellowed teff field – drowsy in the sun – and suddenly, the land drops away again to reveal another angle of that epic gorge.

There, on what felt like the roof of Africa, we find ourselves chatting with a cooperative of small-hold farmers, mothers and herbalists about plant medicines.

“In the old days, herbs were everywhere,” says 76-year-old healer Gashe Abe.“I used to collect them outside my door and they grew naturally in the wild like this.”

He shows us to a rare aloe that likes the exposed crags up here. He was taught about them by his grandfather, a priest herbalist from a small church below town.

“Now, when people ask me for remedies, I have to walk two days down there,” he points to the valley floor, hyena country. “Even in the forest areas, some don’t exist any more at all.”

Between talk of herbs for hypertension and infertility, whooping cough and scorpion sting, the group tell us about the old trees at the monastery. Kosso, with its bitter, peeling bark, is used to expel tapeworm; the ‘Tree of Life’ or African Cherry we saw has properties to cure – among so many ills – urinary and prostate conditions.

Here, plant wisdom is woven with the pattern of the seasons, superstition and village folk tales. Recipes are rarely documented; spoken instead, from one generation to the next. And the raw ingredients, pieces of a landscape that feels so eternal, are disappearing.

“Our medicine is being lost for the children,” says Shikerke, a mother of four. “Now that there are no forests, there’s no rain and without the rain, the farmers can’t be productive like they were,” she says.

“I get sad about it. Already, many of my friends and relatives are leaving for places they’ve never known.”

What can she do? Will she go too someday?

She laughs: “To Addis with its farting cars?” And the women toss their heads with her, laughing into their netelas.

No. She belongs to this place.

“I understand it and I want to tell the stories about the herbs. We have to work together to recover what we’ve lost,” she says. “And here in the mountains, the air is still good – I can breath.”

It’s a reminder, of course: That just being outdoors, in quietly wild places like this one, is good medicine too.

As we pass Debre Libanos on our own journey back to the big smoke, the trees at the church gates – those last warriors in the day’s last light – loom all the more impressive.

As well as stories of saints and divine promises; of bloodshed and pilgrims cured – I hope they’ll stand to reveal many more glimpses, for the day-tripper at least, of everyday life in this mystical place; of rare birds and healing herbs too – sheltered from the high plateau sun.

GETTING THERE: Debra Libanos is easily visited as a full day trip from Addis Ababa. Leave early to avoid traffic out of the city; to give yourself time for a traditional coffee at the Ethio-German Hotel and a late afternoon stop at one of Sululta’s Tej Bets on the way back home. There are many local companies offering day trips. Try: www.africasjeweltours.com or www.toursbylocals.com. Tesfa Tours (www.tesfatours.com), an eco-minded community-centred provider, can be contacted for more extensive hiking and community stays in the area.

OTHER THINGS TO DO:

Walk to the Portuguese Bridge for another impressive vista of the Jemma Valley and sightings of the endemic Gelada Baboons. The bridge is actually believed to have been built in the 1800s by Ras Darge, an uncle of Emperor Menelik. Take the path along the ridge from the Ethio-German Hotel. In the rainy season (June-September), white water gushes under it to tumble into the abyss with force. In the dry season, you can sit on the rock ledge over the gorge – a great picnic spot.

Go deeper. Visit a local family to experience the traditional way of life of the Oromo people. Ask to see how Arake is made here (A white grappa-like spirit, often brewed with herbs like Kosso as a tonic). Many tour companies offer longer hiking and bird watching trips into the valley and the Blue Nile Gorge, as well as community visits.

Roadside shopping: Be sure to stop at any of the roadside stalls for large handwoven baskets and coptic cross pendants carved from the areas pink soapstone. Prices are better than in Addis and money goes directly to the families making them.

Try some of Ethiopia’s best tej (honey mead) and enjoy a traditional azmari performance at honeymoon resort in Sululta, just before the ascent back into Addis. The hotels here also serve great tibbs (barbequed meat with injera) and are popular Sunday spots for young Addis Ababans – great people watching. Tej is said to have medicinal antibiotic properties; good for clearing the skin too. But go easy: High alcohol content means it’s said to ‘have a kick like an Ethiopian mule.’ For a non-alcoholic version, ask for ‘laslasa tej’; a honey and water mixture that has fermented for just a few days without hops. Bottoms up!